John Brill

Splendid Isolation: Pathological Self-absorption Before the Age of Social Media

SPRING/BREAK Art Show, Preview February 28, March 1 - 6, 2017

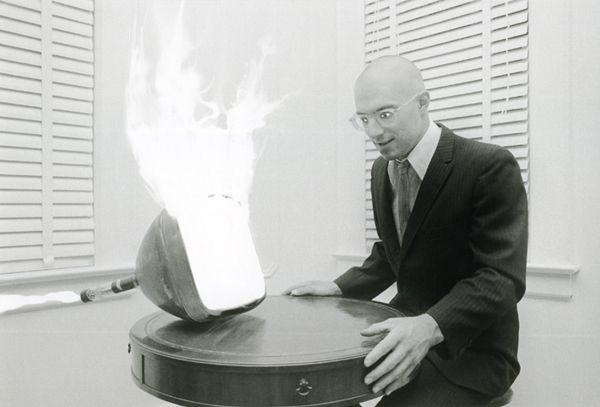

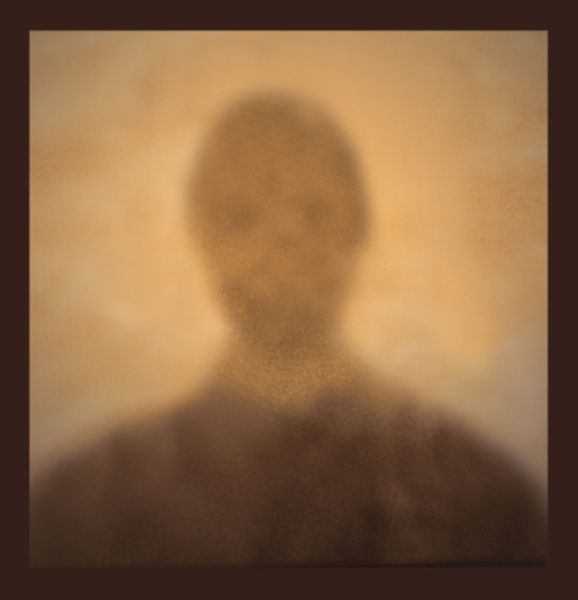

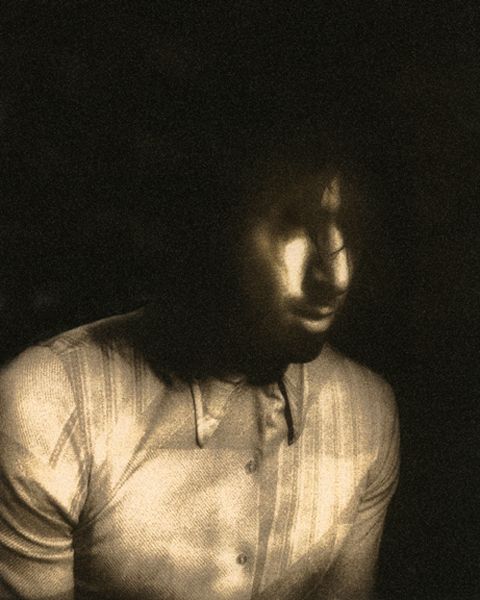

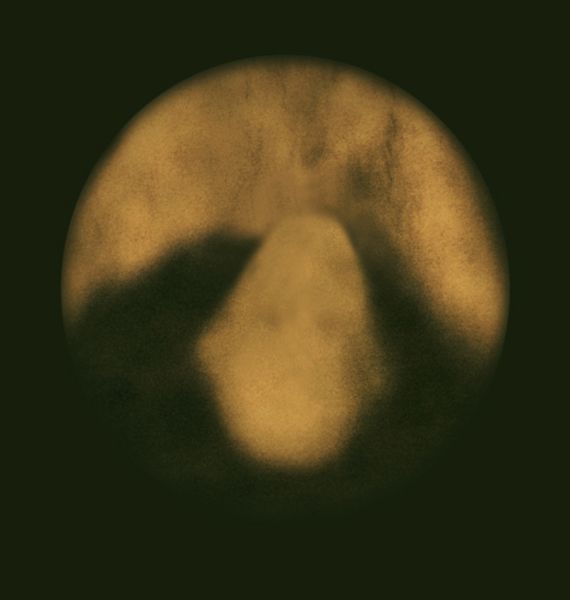

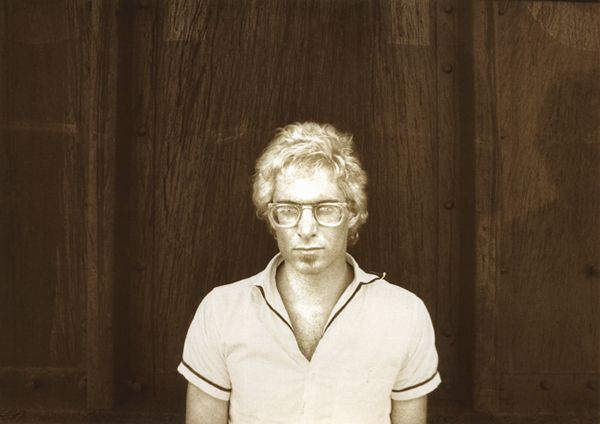

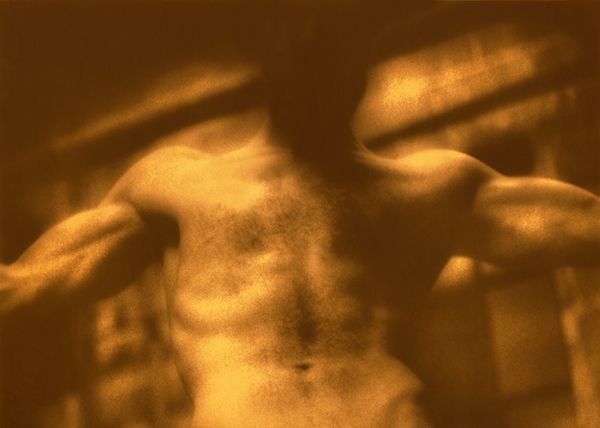

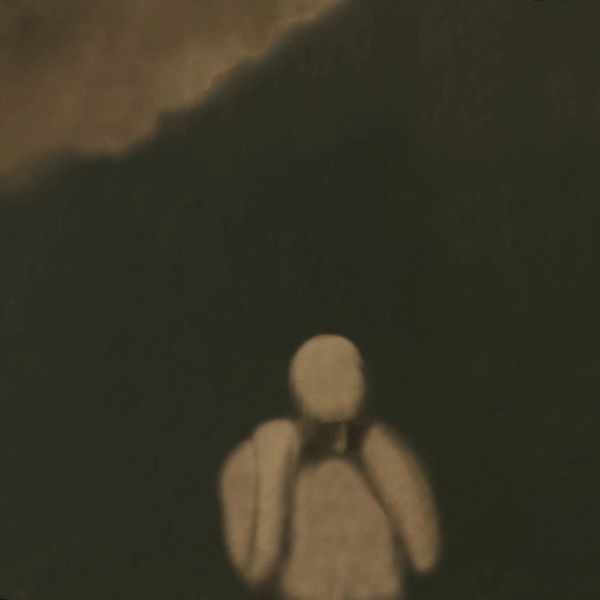

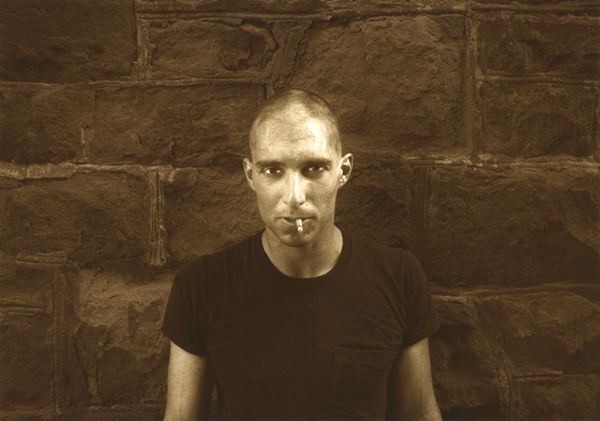

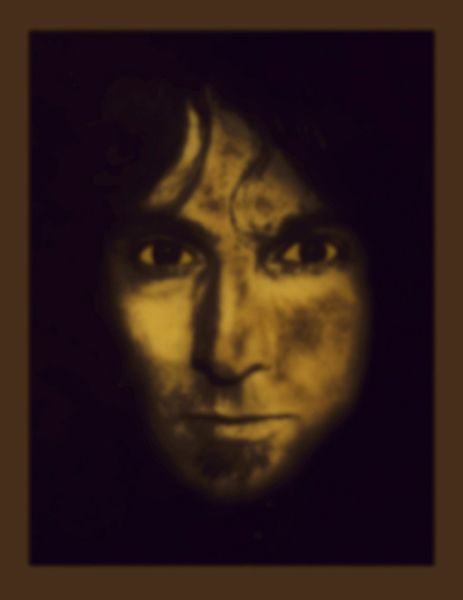

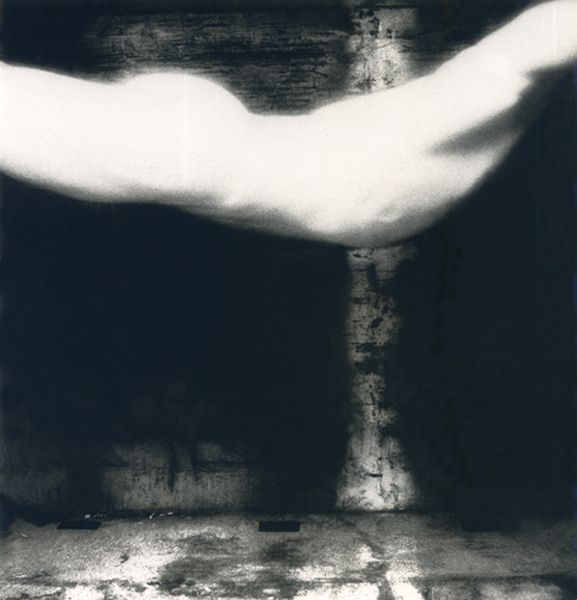

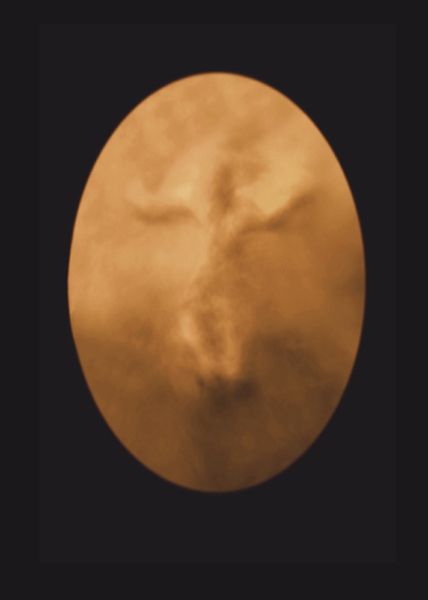

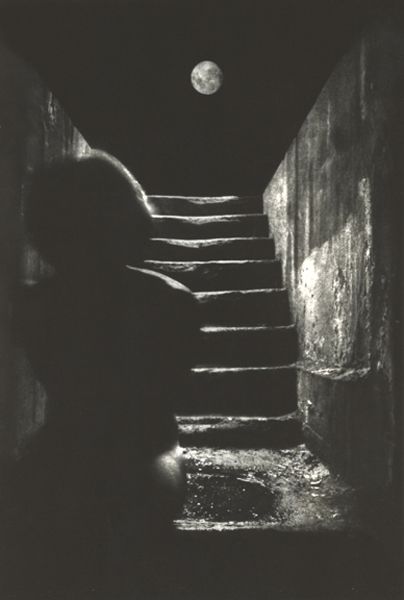

John Brill takes on this year’s SPRING/BREAK Art Show theme, Black Mirror, through a comprehensive and complex installation of hand-crafted photography accompanied by a clutter of heavy wooden furniture, dimly glowing lamps and television screens, and an assortment of the detritus incidental to a lifetime spent making photographs. Toying with the idea of the negotiable nature of autobiography, Brill traces an arc through forty years of work, utilizing autonomous images of scripted self-portraits documented since the 1970s. The resulting body of work—the oxymoronic “manufactured autobiography”—comprises an indecipherable conflation of dualities, all playing out on the sliding scales of autobiography and imagination, reality and fiction, representation and contrivance.

As he discussed recently in a private conversation with the writer Roger Thompson of the photography journalDon’t Take Pictures, Brill had an epiphany two decades ago when curator, Douglas Walla, had encouraged Brill to visit the Gramercy Park Art Fair. In this moment, as he wandered through the hallways of the Gramercy Park Hotel and into the small rooms that housed the participating galleries, he realized that as nice as his photographic prints looked in the “white box” of the gallery, the best context within which his work could operate is real living quarters, whether in hotels, apartments, houses, etc., where he can play upon the expectant and reassuring familiarity of this homey gestalt, and which he can then subvert with dissonant content. This lead to Brill’s first installation in 2002 titled, Endless Summer. In a review of Brill’s 2013 installation, Every Boy’s Dream, published in Hyperallergic, Thomas Micchelli writes about the psychological effect of these environments: “Brill’s pristinely arranged elements…fuse into a vision of crisp, melancholy perfection. But what’s even more intriguing and irresistible, is that even after you’ve looked more closely at Brill’s photographs—bleached and burned images of screaming babies, crucified nudes and radioactive heads—or stared a the grainy video of a ski-masked face floating on an antique TV screen, the installation continues to suck you in without losing its initial welcoming presence. It’s a deliciously ineffable sensation, suspended between piercing images of extreme noir and the silky ambiance of a burnished, incandescent oasis, an exquisite coupling of comfort and dread.”

It’s with this full-fledged knowledge that Brill’s images must reside within their own universe that we’re best able to consider this incarnation of the manufactured autobiography that he constructed specifically around the curatorial theme of Black Mirror. He has stated, “More than anything, doing an installation gives me the opportunity to combine the autobiographical—a lot of stuff is taken right from my residence and work space—with the whimsical, to create a purely fictional reality; some of it is me, some is imagined, and if I’m successful, they mesh seamlessly.” Writing in Don’t Take Pictures, Roger Thompson observed, “When we [live with the dark residue of our histories]…we meet ourselves as caretakers of histories, both real and imagined.”

Brill started making photographic images when he was eight years old, describing his initial assessment of the photographic process as being “like magic.” However concept-driven his current work might appear, his inspiration was and still is derived from the personal images that he long ago saw in photo albums, on people’s walls and dressers, and the slides that his father would project onto screens when his family would get together. Being self-taught was fundamentally imperative for Brill, not in the sense that his work is intentionally de-skilled or lacking in the craft of photography, but quite the opposite, wherein it is fundamental to shaping different ways of seeing the world and the role that image-making plays in shaping ones sensibility and, ultimately, ones identity. Most importantly, being self-taught allowed Brill to enter the mainstream art world with his sensibility fully formed, immune to art world trends and fashion.