John Brill

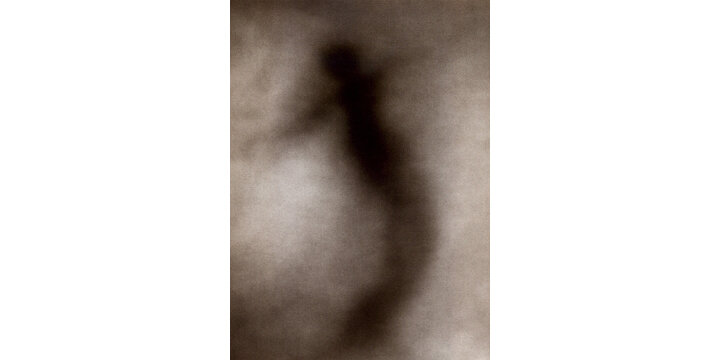

John Brill has been making photographic records of his everyday existence since 1959. Self-taught in photography, Brill's shift to art followed his formal studies within the field of physiological psychology. From the mid-1970s through the 1980s, the artist drove a beer truck in the northeast corner of New Jersey, absorbing the raw visual beauty of a vast industrial wasteland, where he began shooting his seminal series of portraits and self-portraits. Working with an extensive pool of unpaid assistants and models, Brill organized his shoots like performances, frequently involving things set on fire, various states of undress, beer in unlimited supply, and often resulting in large crowds, traffic jams, and, inevitably, the attention of the local police.

At the age of thirty, Brill committed himself to his vision of developing bodies of work that would be psychologically resonant in some universal sense. With no connection to the art world, Brill began to make frequent visits to New York, a divorced truck driver accompanied by his young daughter, and ultimately caught the attention of Bill Arning of White Columns, where he had his first New York solo exhibition. Exhibiting frequently since the 1980s, Brill has produced several thematically coherent, discrete bodies of work includingFamily Holiday Album, Engrams, Ennui, Reliquary—which are the subject of a monograph entitled The Photography of John Brill, written by Leah Ollman—as well as a subsequent series, Cosmophilia.

Brill's most recent series, Bad Memory, is an emotionally charged and intellectually rigorous body of work spanning forty-five years. Utilizing a collection of images the artist made with his first camera—a plastic box camera that he acquired for a few dollars when in third grade—Bad Memory derives from snapshots he began making at the age of eight. Not merely a nostalgic look back at people when they were younger, or places when they were different, Bad Memory is foremost a reinvigoration of what the artist first found to be magical about photography—its ability to manipulate time and space.

Brill's conceptual and subversive approach to the techniques and language inherent in the photographic process stands in clear contrast to current trends in photography. All of the selenium-toned silver prints in this body of work were hand-made by the artist utilizing traditional darkroom methods. Moreover, they are the products of several generations of reworking. This approach to image creation and post-exposure enhancement has conspicuous affinities with the Pictorialists of the early 20th century who, through techniques of soft focus and darkroom manipulation, sought to further break up a picture's sharpness to create images that are more expressive than purely descriptive. In contradistinction to the largely aesthetic goals of the Pictorialists, however, the intended purpose of losing detail here is to render these images as they'd be imperfectly remembered without reference to some external objective record. Working in reverse, Brill has taken existing objective records (the original drugstore prints) and created from them an imperfect (and, ultimately, a partially fictive) subjective recollection—the exact opposite of what the creation of photographic records is normally intended to accomplish. Even the people who appear in these pictures—invariably, close family members—have been obscured to the point of functioning as interchangeable generic props in a subjective psychological landscape. Ultimately, Bad Memory yearns not for an accurate view of the past, but for the prevailing personal sensibility that transcends such a view. This ghostly reality inevitably becomes a deceptively powerful collaboration, as viewers unconsciously seek to impose specificity on Brill's enigmatic imagery.

Brill's intimate handcrafting involves techniques of image creation and production that today have been largely supplanted by digital processes. Even as many of the materials that the artist works with are becoming obsolete and are no longer being manufactured, he continues to create his prints by hand in a darkroom.